Tizon Brown Ware

The most generally recognized marker in the chronological sequence for western San Diego County is the appearance of plain brownware ceramics, usually classified as Tizon Brown Ware. Most of the substantial Late Prehistoric sites in the region contain pottery, and its absence from a site is sometimes taken to be diagnostic of an earlier occupation. No consensus exists as to precisely when ceramics made their appearance in the various portions of the region (cf. Schaefer 2013).

Plain brown ware ceramics dating well before the Late Prehistoric period have been reported from several parts of southern California:

- In Orange County and on Santa Catalina Island, Christopher E. Drover (1971, 1975, 1978; Drover et al. 1979) suggested that plain brown ware ceramics were in use as early as 1500 B.C., based on cultural associations and thermoluminescence dating.

- Judith F. Porcasi (1998) reported additional data on fired clay objects from several portions of southern California and suggested that a ceramic industry had begun as early as 3000 B.C., making it perhaps the earliest known ceramic tradition in the New World.

- Nancy Anastasia Desautels-Wiley (2013) recorded ceramic objects dated to the Middle Holocene at the Encino Village Site (CA-LAN-43) in the San Fernando Valley.

- Melinda Horne and Suzanne Griset (2013) found Middle Holocene ceramics at the Lakeview site (CA-RIV-6069) in the San Jacinto Valley of western Riverside County.

Other investigators have put the first appearance of ceramics in western San Diego County at some time during the last 1,500 years:

- Malcolm J. Rogers (1945) distinguished three ceramic-making Yuman periods in the lower Colorado River area. Only the most recent of these, Yuman III, which he dated to after A.D. 1500, was thought to be represented in western San Diego County.

- Clement W. Meighan (1954:221), discussing the San Luis Rey River area, thought that pottery had arrived “not earlier than 1500 AD and [I] would not be too surprised if future investigation places pottery as late as 1600 or 1700 AD for the Luiseno.” Meighan put the dividing line between the pre-ceramic San Luis Rey I Complex and the ceramic San Luis Rey II Complex at A.D. 1750 (Meighan 1954:223).

- Benjamin E. McCown (1955) gave an estimate of about A.D. 1350 for the appearance of pottery at Temeku in southwestern Riverside County, based primarily on a projection of the rate of sedimentation at that site.

James R. Moriarty (1966:27) proposed that “the earliest known occurrence of pottery [in western San Diego County] is on the Spindrift Site (SDI-39) and dates at 1,270 ± 250 B.P.” The Spindrift date was based on mussel shells and would calibrate, using a marine correction factor of 200 ± 45 years, to a one-sigma (68% probability) range between A.D. 1044 and 1505 and a two-sigma (95% probability) range of A.D. 779-1802. Moriarty did not discuss in detail the association between the radiocarbon date and the ceramics found at the Spindrift Site (cf. Hubbs et al. 1962:235-236).

James R. Moriarty (1966:27) proposed that “the earliest known occurrence of pottery [in western San Diego County] is on the Spindrift Site (SDI-39) and dates at 1,270 ± 250 B.P.” The Spindrift date was based on mussel shells and would calibrate, using a marine correction factor of 200 ± 45 years, to a one-sigma (68% probability) range between A.D. 1044 and 1505 and a two-sigma (95% probability) range of A.D. 779-1802. Moriarty did not discuss in detail the association between the radiocarbon date and the ceramics found at the Spindrift Site (cf. Hubbs et al. 1962:235-236).- Claude N. Warren (1964:142-144) reviewed the radiocarbon evidence for the appearance of pottery in southern San Diego County. He noted that the early Spindrift date was questionable because of possible sample contamination and deposit mixing. He concluded that the evidence suggested pottery had been introduced “earlier than A.D. 1560, later than A.D. 690, and perhaps as late as A.D. 1300” (Warren 1964:144).

- Following up Meighan’s work, D. L. True felt that the date for the appearance of pottery in northern San Diego County could be pushed back somewhat, with its first introduction from Kumeyaay territory as early as A.D. 1200-1300 and its establishment as a regular and important cultural element perhaps during the century A.D. 1500-1600 (True et al. 1974). Later, True (1986) returned to Meighan’s original notion of a later date, suggesting that the transition from pre-ceramic San Luis Rey I to ceramic San Luis Rey II had occurred during the century immediately prior to mission contact, i.e., after about A.D. 1670. In a study of the radiocarbon evidence, True and Georgie Waugh (1983:255) suggested that “pottery was still rare in San Luis Rey contexts well into the 1500s and may have not been common until the 18th century.”

- Ronald V. May (1976, 1978) interpreted a radiocarbon date from the Cottonwood Creek site in the Laguna Mountains as providing an estimate for the advent of ceramics in that portion of the county. The date was reported as 960 ± 80 (May 1976) or 950 ±80 (Linick 1977:34) radiocarbon years (i.e., a one-sigma range of A.D. 1017-1167; a two-sigma range of A.D. 904-1256). The dated sample came from a charcoal lens in the 75-centimeter level of the deposit, overlying a human burial. The earliest ceramics at the site had been found in the 75-80 centimeter level, and the charcoal sample was interpreted as coming from “the earliest ceramic-bearing strata” (May 1978:4). The cultural stratigraphy of the site was interpreted as indicating the presence of an earlier, Amargosan component that contained the human burial, overlain by a later, Hakatayan component with ceramics and cremations. The original submission of the radiocarbon sample by Russell L. Kaldenberg had anticipated that the “date should reflect preceramic horizon assoc[iated] with Mountain aspects of Yuman tradition (Pre-Diegueño or Kumeyaay). Expected date: 1000 BC to AD 1000” (Linick 1977:34). According to this view, the radiocarbon date would represent the latest portion of the preceramic component rather than a period at which ceramics were already present. May also discussed an apparent east-to-west gradient in the times at which pottery appeared within the San Diego region. For the area west of Cottonwood Creek, he cited a personal communication from Paul G. Chace indicating that ceramics were lacking in a layer at Rattlesnake Rockshelter in the Jamul Mountains that dated to A.D. 1300.

- An early radiocarbon date reported by Judy A. Berryman (1981) from the Santee Greens Site, SDI-5669, has been considered a possible marker for the advent of ceramics in western San Diego County. The radiocarbon date of 1220 ±110 B.P. (calibrated one-sigma range, A.D. 680-937; two-sigma range A.D. 637-1021) comes from the lowest level of an excavation unit, a level containing one potsherd. Berryman (1981:405) used the date to propose the “highly speculative” hypothesis that Tizon Brown Ware had originated west of the mountains and had later spread to the east, rather than the reverse.

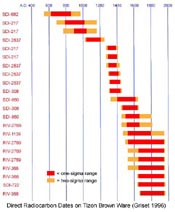

Suzanne Griset (1996) conducted the most thorough investigation of the problem to date. She submitted 22 accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) radiocarbon samples to date directly the carbon residues on brownware sherds from nine sites in San Diego and southwestern Riverside Counties. The earliest date, from the Tomkav Site (SDI-682) on the middle San Luis Rey River, calibrated to a one-sigma range of A.D. 625-850 and a two-sigma range of A.D. 545-950. Slightly later were two dates from the Silver Crest Site (SDI-217) on Palomar Mountain. Griset’s results suggested that the use of pottery in northern San Diego County had begun as early as, if not earlier than, its use farther south. No clear evidence was found for any undeveloped, incipient phase in the local ceramic industry, suggesting that pottery making had been diffused or carried into the region rather than being reinvented locally. Griset also suggested the hypothesis that ceramics may have spread into San Diego County northward from northern Baja California rather than westward from the lower Colorado River.

Suzanne Griset (1996) conducted the most thorough investigation of the problem to date. She submitted 22 accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) radiocarbon samples to date directly the carbon residues on brownware sherds from nine sites in San Diego and southwestern Riverside Counties. The earliest date, from the Tomkav Site (SDI-682) on the middle San Luis Rey River, calibrated to a one-sigma range of A.D. 625-850 and a two-sigma range of A.D. 545-950. Slightly later were two dates from the Silver Crest Site (SDI-217) on Palomar Mountain. Griset’s results suggested that the use of pottery in northern San Diego County had begun as early as, if not earlier than, its use farther south. No clear evidence was found for any undeveloped, incipient phase in the local ceramic industry, suggesting that pottery making had been diffused or carried into the region rather than being reinvented locally. Griset also suggested the hypothesis that ceramics may have spread into San Diego County northward from northern Baja California rather than westward from the lower Colorado River.- Constance Cameron (1999) noted the near absence of Tizon Brown Ware sherds at archaeological sites within Juaneño territory in the northwest corner of San Diego County and southern Orange County. The pattern suggested that pottery-making either had not been adopted prehistorically by the Juaneño or else had spread very late to this area.

PROSPECTS

Future archaeological investigations may be able to determine whether the advent of pottery in the San Diego region occurred any earlier than about A.D. 950; whether there were significant east-to-west and/or south-to-north time lags in the adoption of ceramics within the region; and whether ceramic technology was initially developed independently within the region or introduced in a finished state from outside. Direct AMS dating of sooted sherds can now generally provide more conclusive dates than conventional radiocarbon dating based on contexts and associations. The collection of regional data for late prehistoric habitation assemblages that are substantial in size, functionally diverse, and well-dated, but that lack ceramics, may clarify how late in prehistory a pre-ceramic technology still prevailed in various parts of the region. Evidence in dated sherds for the techniques used in their manufacture may clarify whether the ceramics industry was locally developed or adopted from outside ready-made.