Cultural Anthropology

The rich cultural heritage of the Baja California peninsula has been shaped by its unique geography and ecosystems, a history of isolation and migration, and peoples as rugged and tenacious as the land itself. For the vast majority of human history in the peninsula, native populations have adapted their lives to the arid climate and its coastal, desert and mountain habitats through annual cycles of hunting, gathering and fishing.

The rich cultural heritage of the Baja California peninsula has been shaped by its unique geography and ecosystems, a history of isolation and migration, and peoples as rugged and tenacious as the land itself. For the vast majority of human history in the peninsula, native populations have adapted their lives to the arid climate and its coastal, desert and mountain habitats through annual cycles of hunting, gathering and fishing.  Like other foraging groups, they were often organized in highly mobile extended family bands. Their material culture was simple enough to be packed in a fiber carrying net and moved as different resources-pitaya cactus fruit, acorns, shellfish, deer, just to name a few-came into season. Early accounts describe a diversity of cultures with different languages, oral tradition, religious beliefs, styles of dress, personal ornamentation, diet and customs.

Like other foraging groups, they were often organized in highly mobile extended family bands. Their material culture was simple enough to be packed in a fiber carrying net and moved as different resources-pitaya cactus fruit, acorns, shellfish, deer, just to name a few-came into season. Early accounts describe a diversity of cultures with different languages, oral tradition, religious beliefs, styles of dress, personal ornamentation, diet and customs.

With the Spanish conquest of the Californias beginning some 450 years ago, this way of life would change drastically as native peoples had to adapt to the presence of Jesuit, Franciscan and Dominican missionaries, Spanish military and settlers. Indigenous people responded to these changes in a variety of ways, some of them seeking refuge in remote areas where they continued their hunting and gathering way of life, some mixing in with the new populations, some adding livestock ranching and agriculture to their adaptive strategies.

With the Spanish conquest of the Californias beginning some 450 years ago, this way of life would change drastically as native peoples had to adapt to the presence of Jesuit, Franciscan and Dominican missionaries, Spanish military and settlers. Indigenous people responded to these changes in a variety of ways, some of them seeking refuge in remote areas where they continued their hunting and gathering way of life, some mixing in with the new populations, some adding livestock ranching and agriculture to their adaptive strategies.

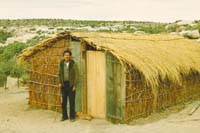

The influences of this common heritage and history have shaped the culture of Baja California’s four surviving native groups. Approximately 1000 Native Baja Californians live in eight indigenous communities of the northern peninsula: the Kumiai in Juntas de Nejí, San Jose de la Zorra, San Antonio Necua and La Huerta; the Paipai in Santa Catarina and San Isidoro; the Cucapá in El Mayor Cucapá and the Kiliwa in Ejido Tribu Kiliwas. These groups all belong to the Yuman family of closely-related languages and cultures, a family that includes other groups of Southern California and Arizona.

The influences of this common heritage and history have shaped the culture of Baja California’s four surviving native groups. Approximately 1000 Native Baja Californians live in eight indigenous communities of the northern peninsula: the Kumiai in Juntas de Nejí, San Jose de la Zorra, San Antonio Necua and La Huerta; the Paipai in Santa Catarina and San Isidoro; the Cucapá in El Mayor Cucapá and the Kiliwa in Ejido Tribu Kiliwas. These groups all belong to the Yuman family of closely-related languages and cultures, a family that includes other groups of Southern California and Arizona.

Today, the cultural landscape of the Baja California peninsula includes:

- the Kumiai, Paipai, Cucapá and Kiliwa Indians, descendents of the Yuman indigenous groups;

- the Rancheros or Californios, living in isolated ranches and rural towns, descendents of the early Spanish settlers and their indigenous neighbors;

- indigenous groups originally from other parts of Mexico, including Yaqui, Mayo, Mixtec, Zapotec, Triqui, Nahuatl and other groups who have migrated to the peninsula primarily during the last century;

- descendents of Spanish, Basque, French, Italian, Russian, German, English, Chinese, North American and other settlers whose surnames can still be found in the farthest reaches of the peninsula;

- mestizos from both urban and rural areas of the Mexican mainland;

- urban populations of the peninsula’s cities

- fishing villages

- transborder communities (living in Mexico, working in the U.S.); and

- the Baja California norteño, a hybrid of several of the previous categories.

Cultural anthropological studies in Baja California have focused primarily on the first category, the native indigenous populations. Due to the tragic extinction of the indigenous groups of the central and southern peninsula, written accounts of those groups can only be found in the pre-ethnographic documents of the Jesuit, Franciscan and Dominican missionaries as well as occasional European explorers and military expeditions (see History).

Cultural anthropological studies in Baja California have focused primarily on the first category, the native indigenous populations. Due to the tragic extinction of the indigenous groups of the central and southern peninsula, written accounts of those groups can only be found in the pre-ethnographic documents of the Jesuit, Franciscan and Dominican missionaries as well as occasional European explorers and military expeditions (see History).

Ethnographic and ethnological reports on the Yuman groups begin in the twentieth century with the works of Peveril Meigs III, William Hohenthal, William Kelly, Frederic Noble Hicks, Roger C. Owen, Ralph Michelsen, Anita Álvarez Williams, Mauricio Mixco, Julia Bendímez, Don Laylander, Michael Wilken, Everardo Garduño, Mario Alberto Magaña Mancillas, Jesus Angel Ochoa Zazueta, and Paul Campbell.

Ethnographic and ethnological reports on the Yuman groups begin in the twentieth century with the works of Peveril Meigs III, William Hohenthal, William Kelly, Frederic Noble Hicks, Roger C. Owen, Ralph Michelsen, Anita Álvarez Williams, Mauricio Mixco, Julia Bendímez, Don Laylander, Michael Wilken, Everardo Garduño, Mario Alberto Magaña Mancillas, Jesus Angel Ochoa Zazueta, and Paul Campbell.

Important contributions to the study of indigenous cultures appear in the special Baja California editions of the Pacific Coast Archaeological Society Quarterly while recent news of the contemporary communities can be found in the CUNA Newsletter (Native Cultures Institute of Baja California).

© 2002 Michael Wilken-Robertson