History

The geographic space known today as the Mexican states of Baja California and Baja California Sur has passed through a long historical sequence which can be grouped into five main periods: ancient history or prehistory (discussed elsewhere), the period of explorations and initial contact (1533-1685), the mission period (1697-1822), the ranch period (1822-1870), and the contemporary period. The geographic space known today as the Mexican states of Baja California and Baja California Sur has passed through a long historical sequence which can be grouped into five main periods: ancient history or prehistory (discussed elsewhere), the period of explorations and initial contact (1533-1685), the mission period (1697-1822), the ranch period (1822-1870), and the contemporary period.

In A.D. 1533, the first contact between Western culture and the peninsula’s indigenous groups took place with the arrival of a group of Spanish mutineers in what is now La Paz. Between that year and 1685 there was a series of attempts at colonization backed by the authorities of New Spain (those of Hernán Cortés and Isidro de Antondo y Antillón being the most notable), as well as innumerable voyages of exploration, coastal trading, piracy, and clandestine exploitation of resources. During this period the contacts were along the coast and of very brief duration, although their impact may have been greater than is currently believed.

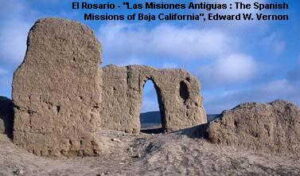

After the Jesuits’ expulsion, they was replaced by Franciscan missionaries who arrived in the peninsula in April 1768. The Franciscans received a royal order to found missions in the extreme north of New Spain (from San Diego Bay to San Francisco Bay) for the defense of the imperial frontier. Given these new challenges, the Franciscans reached an agreement with missionaries of the Dominican order headed by Juan Pedro de Iriarte in Spain to transfer to the Dominicans the former Jesuit missions as well as the newly-founded San Fernando Rey de España de Velicatá. Beginning in 1773, the Dominicans took charge of the Old California field and proceeded to establish missions between Velicatá and San Diego. Between 1773 and 1836, they founded eight new missions in Baja California, in the aboriginal territories of the Cochimí, Kiliwa, Paipai, and Kumeyaay.

By 1870 gold was discovered in Real del Castillo, radically altering the social and economic dynamics of the region. Added to this, the penetration of US capitalism into the area of the Colorado River after the middle of the nineteenth century had also changed the economic relations among the region’s inhabitants, particularly the Cocopa. Before long, the present state of Baja California — known formerly as the Partido Norte (Northern Section) and later as the Distrito Norte (Northern District) of Baja California — was immersed in economic changes due to foreign investment in mines, saltworks, agriculture, commerce, and real estate development. By 1915 this continuing dynamic led to the moving of the state capital to Mexicali, an enclave of cotton and contraband tied to the southwestern United States. Following the serious national unrest caused by the Mexican Revolution, the decades of the 1930s and 1940s brought sweeping changes to the region, with a growing participation of the federal government in local affairs. For indigenous groups this would involve the most aggressive pressure yet against their traditional cultures, because of the idea of homogenization for everything Mexican. Faced with US influence, it was necessary to create or reinforce a Mexican national identity in the border regions, and the indigenous people were considered to be the least Mexican. Furthermore, the agrarian reform movement forced many native groups to concentrate their populations within their last territorial refuges. Among the numerous detailed modern accounts for the various periods of Baja California’s history, the writings of Pablo L. Martínez (1956), W. Michael Mathes (1977), Ignacio del Río (1984, 1985), and Harry Crosby (1994) are fundamental, along with general works such as that of David Piñera Ramírez (1983a). Also, many of the original sources have been made available through compilations and facsimile editions, particularly by W. Michael Mathes, Ernest J. Burrus, Miguel León-Portilla, Eligio Moisés Coronado, and Amado Aguirre, as well as the editions of UNAM, UABC (notably the “Baja California: Nuestra Historia” collection, directed by Aidé Grijalva), UABCS, José Porrúa Turanzas, Doce Calles, and Glen Dawson. © 2002 Mario Alberto Magaña Mancillas (Translated by Michael Wilken-Robertson) |

In 1697, Father Juan María de Salvatierra began a new colonizing project, financed by private donations to the Society of Jesus (the Jesuits) and based on the experiences of Father Eusebio Francisco Kino, which led to the founding the Mission of Our Lady of Loreto. This would be the first of a long series of missions to be founded on the Baja California peninsula, which was then known simply as California. Between 1697 and 1767 the Jesuits founded 16 missions, encompassing practically all of what is today Baja California Sur and beginning their northward expansion with the establishment of Santa Gertrudis, San Francisco Borja and Santa María de los Ángeles. Their impacts affected the native Pericú, Guaycura and Cochimí.

In 1697, Father Juan María de Salvatierra began a new colonizing project, financed by private donations to the Society of Jesus (the Jesuits) and based on the experiences of Father Eusebio Francisco Kino, which led to the founding the Mission of Our Lady of Loreto. This would be the first of a long series of missions to be founded on the Baja California peninsula, which was then known simply as California. Between 1697 and 1767 the Jesuits founded 16 missions, encompassing practically all of what is today Baja California Sur and beginning their northward expansion with the establishment of Santa Gertrudis, San Francisco Borja and Santa María de los Ángeles. Their impacts affected the native Pericú, Guaycura and Cochimí. During the first quarter of the nineteenth century, the mission system began a constantly accelerating process of decay, leading to the closing of most of the missions by the decade of the 1820s. As a consequence, the inhabitants who had settled in the mission areas became cattle ranchers and carried on small-scale agriculture, which was basically a continuation of the mission orchards. As a result of the loss of the priests and neglect by the Mexican authorities, an impoverished ranching society developed with close ties to the indigenous groups, especially in the northern part of the peninsula. During the first three-quarters of the nineteenth century, native leaders-known at the time as captains-were ever more in evidence. The United States’ war against Mexico and the treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo also created new conditions in the extreme north of the peninsula as that area passed from being a marginal internal region to an international border.

During the first quarter of the nineteenth century, the mission system began a constantly accelerating process of decay, leading to the closing of most of the missions by the decade of the 1820s. As a consequence, the inhabitants who had settled in the mission areas became cattle ranchers and carried on small-scale agriculture, which was basically a continuation of the mission orchards. As a result of the loss of the priests and neglect by the Mexican authorities, an impoverished ranching society developed with close ties to the indigenous groups, especially in the northern part of the peninsula. During the first three-quarters of the nineteenth century, native leaders-known at the time as captains-were ever more in evidence. The United States’ war against Mexico and the treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo also created new conditions in the extreme north of the peninsula as that area passed from being a marginal internal region to an international border.